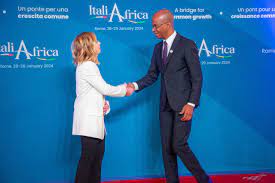

Italian Premier Giorgia Meloni on Monday unveiled Italy’s big development plan for Africa at a summit of the continent’s leaders, aiming to stem the numbers of migrants, diversify sources of energy and forge a new, non-predatory relationship between Europe and Africa.

Meloni declared the summit a successful first step, and top European and United Nations officials said the Italian plan, with an initial endowment of 5.5 billion euros ($5.95 billion), would complement initiatives already under way focusing on climate adaptation and clean energy development in Africa.

But the African Union Commission was more cautious, telling the summit that African countries would have liked to have been consulted beforehand and didn’t want more empty pledges.

The government’s plan, named after Enrico Mattei, founder of state-controlled oil and gas company Eni, seeks to expand cooperation with Africa beyond energy and amounts to a new philosophy and method, Meloni said.

Asked at a closing news conference about the lack of consultation with African leaders, Meloni acknowledged she may have “erred” in being too specific in describing pilot projects in her introductory speech.

But she said the summit provided African leaders with a preliminary outline of Italy’s philosophy backed by concrete examples, that will be brought forward in a shared partnership.

“The summit is fundamental for sharing not only the strategy but also, in short, the final definition of the project,” she said.

Two dozen African leaders, top EU and U.N. officials and representatives from international lending institutions were in Rome for the summit, the first major event of Italy’s Group of Seven presidency.

Italy, which for decades has been ground zero in Europe’s migration debate, has been promoting its development plan as a way to create jobs and opportunity in Africa and discourage its young people from making dangerous migrations across the Mediterranean Sea.

The plan involves pilot projects in areas such as education, health care, water, sanitation, agriculture and energy infrastructure.

Meloni, Italy’s first hard-right leader since the end of World War II, has made curbing migration a priority of her government.

But her first year in power saw a big jump in the numbers of people who arrived on Italy’s shores, with about 160,000 last year.

As the summit got underway, the International Organization for Migration reported that nearly 100 people had died or gone missing in the Mediterranean so far this year, twice as many as in the same period of last year, which was the deadliest since 2016.

Agencies